PART 36: PRACTICAL LAW VIDEO SPECIAL

In this Issue there are links to two videos that I have recorded for Practical Law, together with the transcripts of those interviews.

The links to the videos are only available until Thursday, 2 May 2024, and I thank Practical Law for allowing me free use of those for that period.

Part 36 offers: Overview

In this video, I describe the purpose and benefits of making Part 36 offers to settle and outline the basic requirements when making such offers and explain the implications of Part 36 being a self-contained code.

I look at the consequences of accepting a Part 36 offer late and of not accepting a Part 36 offer at all.

This video is 10 minutes long and does not deal with fixed costs cases, which are in a separate video.

Here is the link

– https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-043-0756

Part 36 Offers: Practical Differences Under the Fixed Recoverable Costs Regime

This is 16 minutes long and the video chapters are as follows:

- Part 36 under the fixed recoverable costs regime.

- Costs consequences if a claimant matches or beats its own Part 36 offer.

- Costs consequences if a claimant fails to beat a defendant’s Part 36 offer.

- Late acceptance by a defendant in a fixed recoverable costs case.

- Late acceptance by a claimant in a fixed recoverable costs case.

- Areas of uncertainty due to contradictory rules.

- Aspects of the rules which need rewriting.

Here is the link

– https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/w-043-0759

TRANSCRIPT OF PRACTICAL LAW VIDEO: PART 36 OFFERS: OVERVIEW

TRANSCRIPT OF PRACTICAL LAW VIDEO: PART 36 OFFERS: PRACTICAL DIFFERENCES UNDER THE FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS REGIME

INSURER TO CUT OUT LAWYERS – SOME THINGS NEVER CHANGE

Here is an article from the Law Society’s Gazette – 9 December 2004

Some things never change…

FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS: APRIL 2024 AMENDMENTS: PRACTICAL LAW VIDEO HERE UNTIL 19 APRIL 2024

Here is a link to my video recorded for Practical Law on Fixed Recoverable Costs: April 2024 Amendments.

This is only available via this link until this Friday, 19 April 2024, and is 25-minutes long.

Here are the subjects it covers:

- Inflation uprating of fixed recoverable costs.

- Changes relating to advocates’ fees.

- New rules regarding contracting out of fixed recoverable costs.

- Notable omission in relation to clinical negligence.

- Rule clarifications: inquest proceedings and company restorations.

- Existing challenges with the fixed recoverable costs regime.

Fixed Costs Zoominars : Next one this afternoon!

I am conducting a series of three 1-hour Zoominars dealing with Fixed Recoverable Costs and the cost for all three is £150 plus VAT, it is a £180.

The first one took place on 16 January 2024 and a link to the recording is available and covers amongst other things:

– Contracting Out;

– Inquest Costs;

– Company Restoration Proceedings Costs;

– Counsels’ Fees on Late Settlement;

– Conflicting Provisions on Settlement Pre-Issue;

– Defendants’ Right to Costs if Discontinued Pre-Issue;

– Part 36;

– Track Allocation and Band Assignment;

– The Conundrum re Civil Proceedings unissued by 1 October 2023.

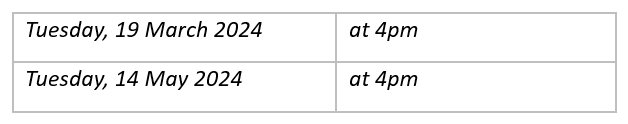

The next ones are:

Tuesday, 19 March 2024 at 4pm

Tuesday, 14 May 2024 at 4pm

The one this afternoon 19 March 2024 will cover the amendments to the Fixed Recoverable Costs Scheme coming in on 6 April 2024, including:

- Inflation uprated figures for all fast track and intermediate track claims, and the Noise-Induced Hearing Loss Scheme

- Advocates Fees in Cases Settled late or Vacated

- Fixed Recoverable Costs on Assessment

- Fixed Costs in Part 8 (Costs only claims)

- Inquests

- Restoring a Company to the Register

- Clinical Negligence

- Directions

- Length of Expert Reports

- Part 36

- Contracting Out

- Case Management

- Future Developments

As many colleagues as you like from your organisation can attend and recordings sent whether or not you attend.

To book a place, click here.

Fixed Recoverable Costs Autumn 2023 Extensive Course Material

You can also purchase my detailed Course Material on Fixed Recoverable Costs from Autumn 2023, fully updated to take account of recent changes.

The cost is £150 plus VAT total £180, and you can buy here.

Documents Subscription

I have updated completely the Documents, Videos, Agreements and Advices Menu and this contains 39 new Conditional Fee Agreements suitable for Fixed Recoverable Costs cases, covering Civil Litigation as well as Personal Injury and Clinical Negligence.

You can purchase the entire hyperlinked suite of all documents, and not just the Conditional Fee Agreements, here for £2,000 plus VAT for the first year.

If you wish to renew for 2025 and beyond the cost reduces to £1,000 plus VAT to reflect the fact that much of the benefit is gained in the first year.

This subscription includes the thrice weekly Newsletter Kerry On Costs, Regulation, Legal Systems And So Much More…

Kerry on Costs Regulation Legal Systems and So Much More

The above Newsletter subscription itself costs £500 plus VAT for each year and you can purchase it here.

Subscription to the Documents Service, or the Newsletter Service, includes free attendance for as many people as you want from your organization at the two upcoming Zoominars, plus the recording of the Zoominar which has already taken place.

CLOSE THE COMMERCIAL COURT TO FOREIGN LITIGANTS UNTIL COUNTY COURT BACKLOG IS CLEARED

This appeared in the newsletter KERRY ON COSTS, REGULATION, LEGAL SYSTEMS AND SO MUCH MORE… which comes out electronically 2 or 3 times a week. Subscription for a year – so to 31 March 2025 is £500 plus VAT – total £600.

You can find out more and book here.

If you would like 4 sample copies free, please contact Kerry on kerry.underwood@lawabroad.co.uk.

All people in your organisation are included in that price. It includes free access to Zoominars – the next ones-on Fixed Costs are on

plus a recording of the one that has already taken place.

The Ministry of Justice: Civil Justice Statistics Quarterly published in Issue 230, showed, amongst other things, that the average time for a Small Claim to reach trial or first hearing is now 55.8 weeks, that is over one year.

That is an average and there is anecdotal evidence that in some courts in Southern England the time is around two years.

The figures appear not to take into account hearings that are adjourned, because there is no Judge to hear them.

Any which way, it is a hopeless failure of the system.

Throw in the Pre-Action Protocols, and you can add another three months.

The reality is that anyone can avoid paying a debt for the best part of 18-months simply by filing some sort of Defence, and even if they lose at the end of the day, or more likely admit shortly before trial, no costs are payable.

The Small Claims Limit is £10,000, which is not a small amount for most individuals or small businesses.

These delays do huge harm to the functioning of businesses and the domestic economy generally, which is driven by small- and medium-sized enterprises.

Evening and weekend courts should be set up to clear this backlog with former judges being brought in to assist.

It is this sharp end that really matters, not the big fee Commercial Court where 64% of cases had at least one non-UK party and 40% were entirely non-UK based.

They may earn fat fees for lawyers, but this is an intolerable use of resources when the County Courts are literally and metaphorically falling apart.

Am I saying that Commercial Court Judges should be freed up to assist the County Court backlog?

If necessary, yes.

FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS – CPR 45.13

This appeared in the newsletter KERRY ON COSTS, REGULATION, LEGAL SYSTEMS AND SO MUCH MORE… which comes out electronically 2 or 3 times a week. Subscription for a year – so to 31 March 2025 is £500 plus VAT – total £600.

You can find out more and book here.

If you would like 4 sample copies free, please contact Kerry on kerry.underwood@lawabroad.co.uk.

All people in your organisation are included in that price. It includes free access to Zoominars – the next ones-on Fixed Costs are on

plus a recording of the one that has already taken place.

In my piece – PART 36, FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS AND CLAIMANT’S LATE ACCEPTANCE – I looked, amongst other things, at the fact that both parties can get costs from each other for the same work!

Simon Gibbs, the Expert Defence Costs Lawyer, whose excellent blog is here, in his piece – Fixed Recoverable Costs – CPR 45.13 looked at the apparently unintended prospect of a double sanction for unreasonable conduct, which can arise because both parties get costs, and as we have seen in the lengthy article above, both parties can get costs for the same work in the same stage, as that is how late acceptance of a Part 36 offer works.

Thus, a claimant accepts late in the same Stage that the offer expired.

Both parties get full costs from the other side for all the work in that stage (yes, honestly!)

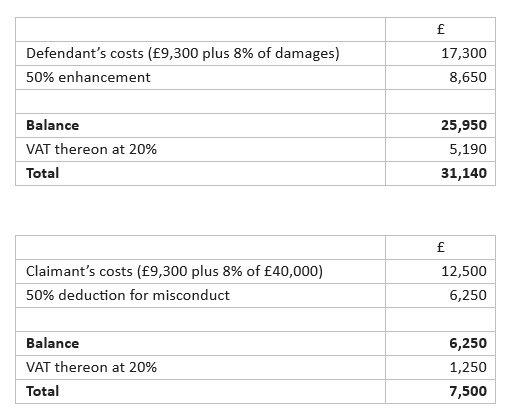

Let us say that the defendant successfully argues unreasonable conduct.

Does the defendant get both a 50% increase in its own costs for that Stage, and a 50% reduction in the costs that it has to pay the claimant for that Stage?

On the face of it, yes.

As will be seen above, we have no idea whether the defendant gets costs based on the amount accepted, or claimed, as there are directly contradictory rules on this point within the Civil Procedure Rules.

Let us make it easy and take a Stage 1 personal injury case, where costs are fixed, as compared with a civil case where costs are capped, and not fixed, which makes it much more complicated.

The claimant claims £100,000 and accepts late for £40,000.

The claimant’s conduct is held to be unreasonable.

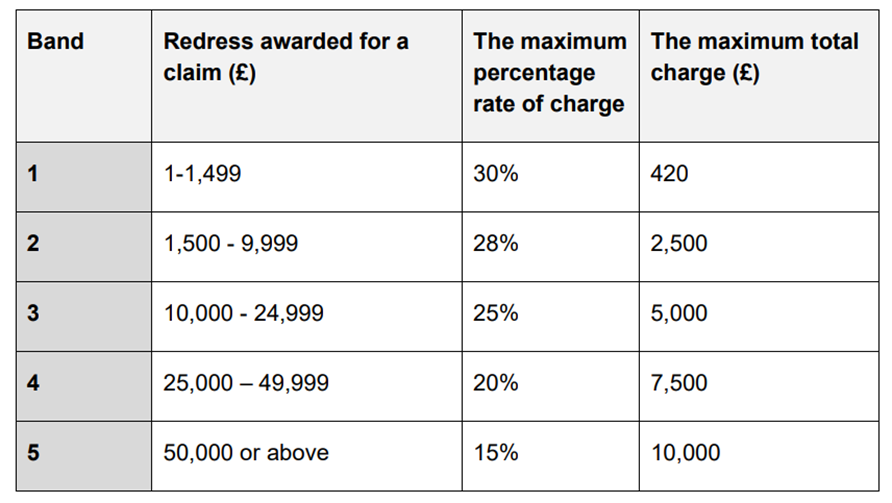

These are the consequences:

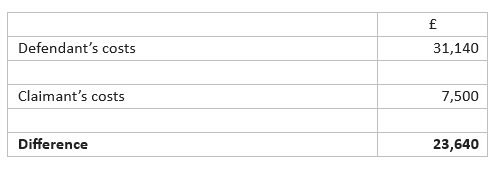

Difference between defendant’s costs and claimant’s costs:

Script of explanation to client:

I have good news for you. We have won your case and accepted the other side’s offer of £40,000 which you were very happy about.

I was a bit busy and was a few minutes late accepting their offer, and I am afraid that has cost you £23,640.

I was five minutes late and so the defendant was on an hourly rate of £283,680. Sorry!

You will receive only £16,360 from the other side.

The good news is that I capped all my charges to you at 30% of damages, so that is £12,000.

This means that you will receive £4,360 out of the £40,000.

PART 36, FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS AND CLAIMANT’S LATE ACCEPTANCE

This appeared in the newsletter KERRY ON COSTS, REGULATION, LEGAL SYSTEMS AND SO MUCH MORE… which comes out electronically 2 or 3 times a week. Subscription for a year – so to 31 March 2025 is £500 plus VAT – total £600.

You can find out more and book here.

If you would like 4 sample copies free, please contact Kerry on kerry.underwood@lawabroad.co.uk.

All people in your organisation are included in that price. It includes free access to Zoominars – the next ones-on Fixed Costs are on

plus a recording of the one that has already taken place.

I am very grateful to Simon Gibbs, the Expert Defence Costs Lawyer, whose excellent blog is here, for his input into this piece, and, frankly, for putting me right.

I had assumed, wrongly, that a claimant’s late acceptance within the same stage of a Fixed Recoverable Costs case would have no adverse costs consequences as the moment the claimant enters that stage, they get the full fixed costs for that stage and that remains the case, and the sum remains the same, until the next stage is entered.

That would seem to me logical and sensible, which is no doubt why I wrongly assumed that that was the end of the story.

What in fact happens, bizarrely in my view, is that late acceptance, even by a day, means that both parties get Fixed Recoverable Costs from each other for that stage.

What the Civil Procedure Rules could have said, but do not, is that where a claimant accepts a defendant’s offer after the expiry period, but within the same stage that it was made, then neither party gets costs for that stage.

That is not what it says, and you might think that it is the same hill of beans, as both parties getting costs from each other for the same stage, cancels each other out. That is not necessarily the case.

Not only does it mean that the claimant gets nothing for that stage, but they will actually get less than nothing as the defendant’s costs for that stage will always be higher than those of the claimant.

I make that statement boldly, but I will look later at the stark contrasts between CPR 45 and CPR 36, which means that I simply do not know if that is correct.

The logic behind me saying that is that the claimant receives costs on the basis of the amount settled for, that is the value of the Part 36 offer, whereas the claimant pays costs on the basis of the sum claimed.

It is certainly the case that the claimant receives costs on the basis of the amount settled for, but in a Part 36 case, it is unclear whether the claimant pays costs on the basis of the sum claimed, or the sum settled for, and I look at that later.

It is hard to think of any case where the Part 36 offer by the Defendant is going to be for everything claimed by the claimant, and therefore, one would always expect the amount settled for to be less than the amount claimed.

The relevant Rules in relation to this point are CPR 36.23(3), (8), and (9).

These read:

“(3) Subject to paragraphs (4) and (5), where a defendant’s Part 36 offer is accepted after the relevant period—

(a) the claimant is entitled to—

(i) the fixed costs in Table 12, Table 14 or Table 15 in Practice Direction 45 for the stage applicable at the date on which the relevant period expired; and

(ii) any applicable additional fixed costs allowed under Section I, Section VI, Section VII or Section VIII incurred in any period for which costs are payable to them; and

(b) the claimant is liable for the defendant’s costs in accordance with paragraph (8).

(8) Subject to paragraph (9) where the court makes an order for costs in favour of the defendant, the defendant is entitled to—

(a) the fixed costs in Table 12, Table 14 or Table 15 in Practice Direction 45 for the stage applicable at the date of acceptance; and

(b) any applicable additional fixed costs allowed under Section I, Section VI, Section VII or Section VIII incurred in any period for which costs are payable to them,

less the fixed costs to which the claimant is entitled under paragraph (3)(a)(i) or (4).

(9) Where—

(a) an order for costs is made pursuant to paragraph (3); and

(b) the stage applicable at the date on which the relevant period expires and the stage applicable at the date of acceptance are the same,

the defendant is entitled to the fixed costs applicable to that stage.”

Thus, the claimant does indeed get all its fixed costs of the stage in which the Part 36 offer is accepted, whether accepted in time, or late.

That is the effect of CPR 36.23(3)(a)(i).

So far, so good.

However, CPR 36.23(3)(b) provides that the claimant is liable for the defendant’s costs in accordance with Paragraph (8).

Paragraph (8) provides that where the court makes an order for costs in favour of the defendant, the defendant is entitled to the fixed costs for the stage applicable at the date of acceptance less the costs due to the claimant for the same stage.

The very fact that the Rules state that, suggests that the costs may be different, for the reasons set out above, that is a claimant getting costs on the basis of the amount settled for, and the defendant getting costs on the basis of the amount claimed.

Otherwise, as mentioned above, it would have been far simpler to say that where an offer is accepted late within the same stage, neither party gets costs for that stage.

Paragraph (8) is subject to Paragraph (9) which provides at (b) that where the stage application at the date on which the relevant period expires and the stage applicable at the date of acceptance are the same, the defendant is entitled to the fixed costs applicable at that stage.

Again, that suggests that the defendant gets its costs on the basis of the amount claimed, and not settled for, which is what CPR 45.6(2) and (3) say and I set this out below:

“(2) For the purpose of assessing the costs payable to a defendant by reference to the fixed costs in Table 12 and Table 14—

(a) “value of the claim for damages” and “damages” shall be treated as references to the value of the claim, as defined in paragraph (3); and

(b) if the claim is discontinued, a reference in Table 12 or Table 14 to the stage at which a case is settled shall be treated as a reference to the stage at which the case is discontinued.

(3) For the purposes of paragraph (2)(a), ‘the value of the claim’ is—

(a) the amount specified in the claim form, without taking into account any deduction for contributory negligence, but excluding—

(i) any amount not in dispute;

(ii) interest; or

(iii) costs;

(b) if no amount is specified in the claim form, the maximum amount which the claimant reasonably expected to recover according to the statement of value included in the claim form under rule 16.3;

(c) if the claim form states that the claimant cannot reasonably say how much is likely to be recovered—

(i) £25,000 in a claim to which Section VI applies; or

(ii) £100,000 in a claim to which Section VII applies;

(d) if the claim has no monetary value—

(i) the applicable amount in rule 45.45(1)(a)(ii) in a claim to which Section VI applies; or

(ii) the applicable amount in rule 45.50(2)(b)(ii) in a claim to which Section VII applies; or

(e) if a claim includes both a claim for monetary relief and a claim which has no monetary value, the applicable amount in sub-paragraph (d) taken together with the applicable monetary value in sub-paragraph (a), (b) or (c).”

I return to that subject later.

So, that appears to be that, although I am not sure what CPR 36.23(9) brings to the table that is not already covered by CPR 36.23(8).

The Effect

A non-personal injury claimant receives an offer in Stage 1 which expires a day before the Defence is filed, triggering the matter to go into Stage 3, something which the defendant can control and engineer.

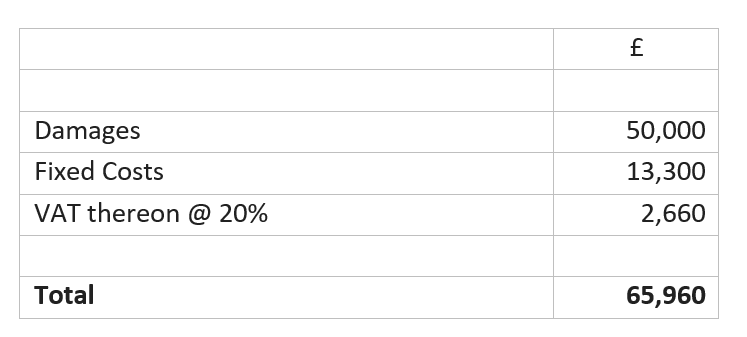

The claim is for £100,000 and settles for £50,000 due to uncertainties which both parties accept and which would have led to the matter being assigned to Complexity Band 4.

The claimant accepts in time.

The claimant will get Stage 1 costs to be assessed, not fixed in non-personal injury matters, but subject to a cap at the Fixed Recoverable Costs sum for Stage 1.

So, the client gets £50,000 plus assessed costs subject to a cap of £13,300, plus VAT, that is

£9,300; plus

8% of damages; plus

VAT.

Let us assume that the claimant accepts two days late and is now in Stage 3, because the filing of the Defence has moved the matter from Stage 1 to Stage 3.

Please do not get me started on why Stage 3 is called Stage 3 rather than Stage 2. I have written about that extensively, and this piece will be long enough in any event.

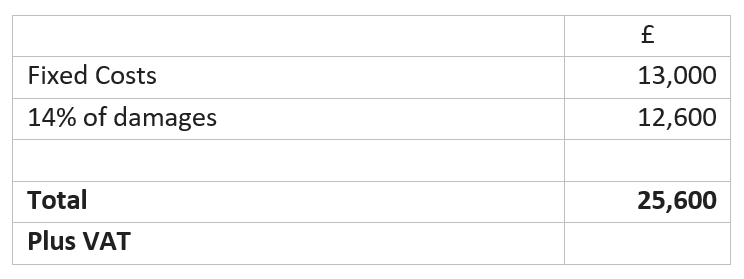

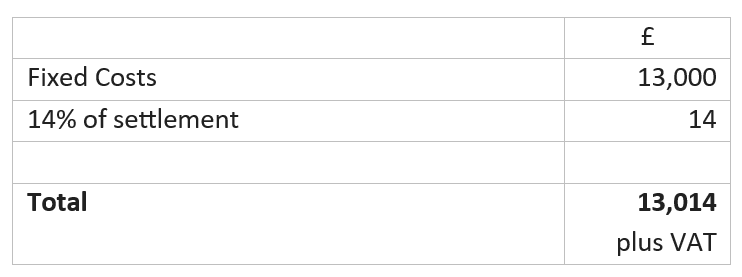

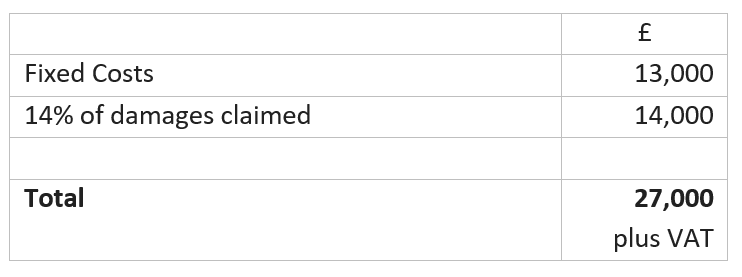

It appears that the defendant gets £27,000, being the fixed fee of £13,000; plus

14% of the £100,000 damages claimed.

That is subject to a further discussion below.

What does the claimant get?

I do not know.

The maximum is clearly £13,300 as set out above, but whether that becomes fixed, and not capped, as the matter is now in Stage 3, retrospectively fixed in Stage 1 costs, I do not know.

As the time for acceptance expired in Stage 1, is the claimant only entitled to assessed costs on the basis of work done, subject to the Stage 1 cap, or to fixed Stage 1 costs?

Either way, the claimant is at least £13,700 plus VAT worse off, so that is £16,440, or one third of the damages in this example.

In personal injury cases, the Stage 1 costs are fixed, and Qualified One-Way Costs Shifting applies.

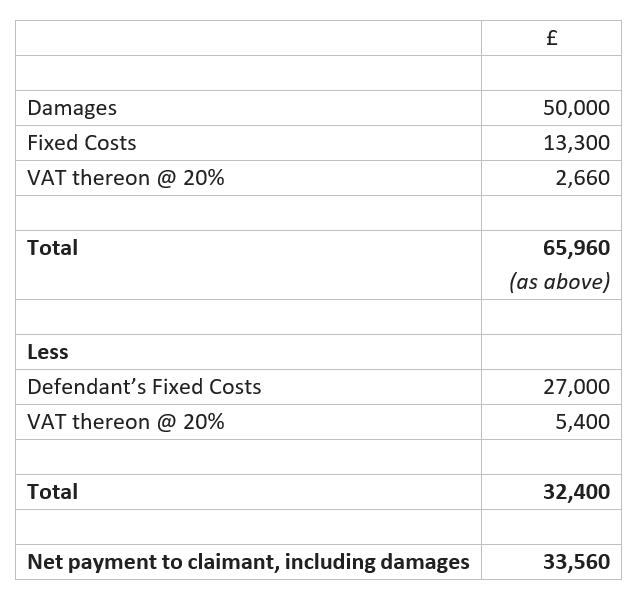

If the claimant accepts in time, she/he gets:

If the claimant accepts late in Stage 3, then the position is:

Thus, two days, when maybe no work at all was done, costs to the claimant of £33,560, that is virtually half the award.

What happens if the claimant accepts late in the same Stage – let us assume Stage 1 – and proceedings have been issued?

I make this qualification about proceedings being issued as it remains unclear as to whether a defendant can ever recover costs in an un-issued matter.

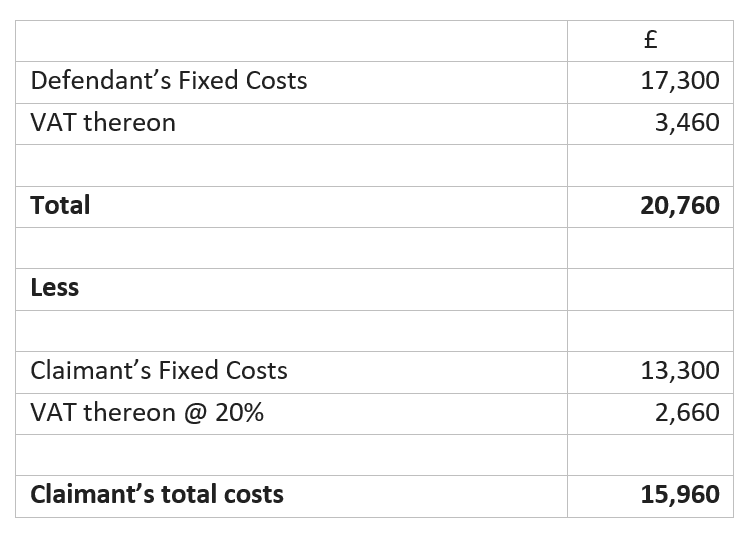

In a personal injury claim on the above figures, it would look like this:

Thus, the claimant owes the defendant £4,800 which will be set off against damages.

Incidentally, the claimant’s solicitor could presumably claim a success fee of up to £12,500, being 25% of the damages, and less than the maximum 100% uplift on Solicitor and Own Client costs, even on a recovered costs basis, even though in reality, the claimant is paying out costs to the defendant!

In a non-personal injury case, each side’s costs will be assessed if the matter resolves in Stage 1, but after expiry of time for accepting the defendant’s Part 36 offer.

However, the claimant’s costs would be capped at £15,960 including VAT and the defendant’s costs at £20,760 including VAT, even if the defendant had done only a fraction of the work that the claimant had done.

In non-personal injury matters, there is no damages-based cap on the amount of the success fee that the solicitor can charge, and therefore, the success fee alone in the above case could be £15,960 even though in reality, the claimant is receiving no costs, and is paying out £4,800 net to the defendant.

There will be some interesting Solicitor and Own Client challenges under the Solicitors Act 1974 coming up.

Having said all of that, I am not sure that I am correct in stating that the defendant gets Fixed Costs on the basis at the amount claimed.

This is unquestionably the general position in Fixed Recoverable Costs cases, as that is what CPR 45.6(2) and (3) say, and I have set those provisions out above.

However, in a stand-alone throw away provision, CPR 36.23(6) says:

“(6) Fixed costs shall be calculated by reference to the amount of the offer which is accepted.”

It is not clear whether that refers only to a claimant’s costs, or to both parties’ costs, including the defendant’s costs, and CPR 36.23(6) appears after CPR 36.23(3) which I have set out above, and which deals with late acceptance.

That would have the bizarre effect that the more the defendant’s solicitors get the settlement down, the less they get in costs, albeit the defendant will be paying lower damages.

So, £100,000 is claimed, and the claimant accepts £90,000 late in Stage 3 when the time for accepting expired in Stage 1.

The defendant’s costs are £25,600 plus VAT comprised of:

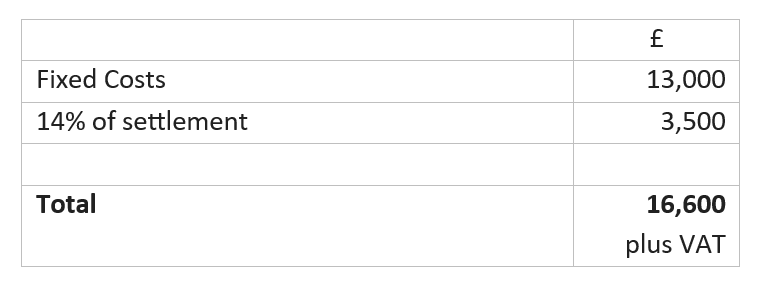

Same claim, same timescales, but the claim settles for £25,000.

The defendant gets:

Thus, for achieving a far better result for the defendant, the defendant’s Fixed Recoverable Costs are reduced by £9,500 plus VAT.

If the claimant accepted £100, then the defendant would get:

If the claimant accepted nothing and discontinued the claim, then the defendant would get:

In any event, there is no doubt that rather than softening the effect of late acceptance within the same stage, as I originally thought, the new scheme is very much harder on late accepting claimants than the old scheme.

A late accepting defendant still suffers no penalty whatsoever.

With all due modesty, I reckon I know a little bit about Fixed Recoverable Costs, and a little bit about Part 36.

I have not got a scooby-doo what the position is.

I repeat my thanks to Simon Gibbs – over to you Simon.

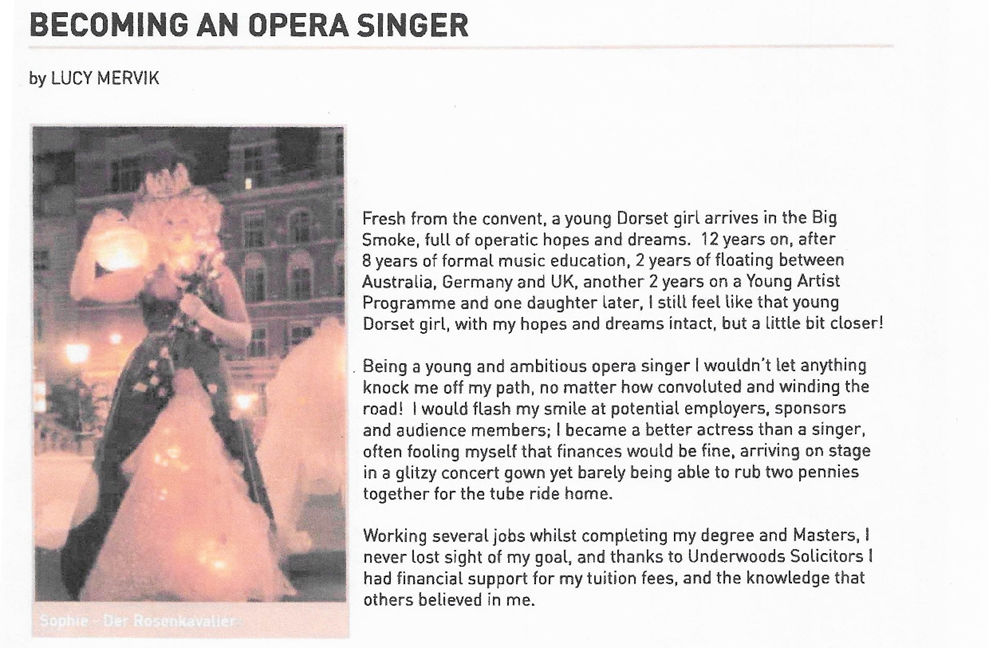

OPERA, CAPE TOWN OPERA AND LUCY MERVIK AND BECOMING AN OPERA SINGER

I am currently in the Western Cape of South Africa and enjoying many events with Cape Town Opera and I am delighted to be a gold sponsor and also involved with the UK Friends of Cape Town Opera.

I was over 40 before I had any involvement in opera and that involvement started with a young opera singer from Dorset, Lucy Mervik, who was seeking sponsorship and support.

So, thank you Lucy, and Cape Town Opera.

Here is a lovely piece that Lucy wrote a little while ago.

A CHRISTMAS CAROL BY THE HIGH COURT

Not a good week for employment tribunals with the Government proposing to re-introduce fees for claims.

Below I reproduce my piece from 18 December 2014 on the previous scheme- A Christmas Carol by the High Court – which scheme was outrageously upheld by the High Court and Court of Appeal, but torn to shreds by the Supreme Court.

Why not just deport Employment Tribunal Applicants to Rwanda?

The new scheme will last until around 10am on the day after the new Government is elected.

Here is my blog about the last Employment Tribunal Fee scheme – read by the Supreme Court I understand.

A CHRISTMAS CAROL BY THE HIGH COURT

Given the Supreme Court decision this morning unanimously to allow the appeal against the Administrative Court’s refusal to judicially review Employment Tribunal fees, this post I wrote at the time needs another airing.

Scene:

Any solicitor’s office in the country (except the Strand).

Solicitor:

So, Ms Peasant you have been sacked because you are pregnant and you have come in for a free interview. Typical of your sort if I may say so.

Client:

It’s so unfair. I want to bring a claim. You do no win no fee don’t you?

Solicitor:

WE do. The State doesn’t. Tribunal fees are £1,200.00 win or lose.

Client:

I haven’t got that sort of money! I am unemployed. I’ve been sacked.

Solicitor:

Come, come now. I am an employment lawyer. I know the minimum wage is £6.50 an hour. Easy to remember; it is one hundredth of what I charge – 200 hours work and you have the fee, unless we need to appeal. Cut out the foreign holidays. Sack the nanny – she won’t be able to afford the fee to sue you. My little joke!

Client:

My Mum looks after the children. We only just got by when I was working.

Solicitor:

There I can help you. You need to prioritise your spending. The High Court has said so. Eat your existing children – Swift said that and he was a clever man, but you peasants don’t read you just watch Sky.

Client:

We don’t have Sky. Murdoch is nearly as right wing as the High Court.

Solicitor:

Go down the library and read Swift.

Client:

They’ve closed the library.

Solicitor:

Have an abortion. Save you money and I might be able to get your job back.

Client:

I don’t want an abortion. Anyway they’ve closed the clinic.

Solicitor:

Find a rich man.

Client:

I am married. My husband was sacked for complaining about my treatment at work.

Solicitor:

Oh then he has a claim as well then. Another £1,200.00 mind.

Client:

I’ve had enough!

Solicitor:

I advise on the law; I don’t make it. I want to read to you what the High Court said:

“The question many potential claimants have to ask themselves is how to prioritise their spending; what priority should they give to paying fees in a possible legal claim as against many competing and pressing demands on their finances?”

It goes on a bit but basically do you want to bring a claim or eat and feed and clothe your children?

Client:

But no-one should have to make that choice in Britain in 2014.

Solicitor:

That’s where you are wrong. The court said:

“The question is not whether it is difficult for someone to be able to pay – there must be many claimants in that position – it is whether it is virtually impossible and excessively difficult for them to do so”.

Client:

That’s wicked.

Solicitor:

That’s the High Court. Lord Justice Elias is paid £198,674.00 and Mr Justice Foskett £174,481.00 so they know all about having to count the pennies.

Client:

Surely Labour will change all this.

Solicitor:

Nope.

Client:

I think I will vote for the Fascists then.

Solicitor:

They tried that in Germany. Didn’t do them much good. Nice rallies mind.

Client leaves. Solicitor hums the Horst Wessel. There is a muffled explosion. The local court is in ruins.

CIVIL PROCEDURE RULES: VALUE OF CLAIM: CPR 16.3, PRACTICE DIRECTION 7A 3.5, FORM N1A: A COMPLETE MESS

Fixed Costs Zoominars

I am running three Fixed Costs Zoominars on the following dates:

– Tuesday, 16 January 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 19 March 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 14 May 2024: 4pm to 5pm

Recordings of the Zoominars will be sent whether or not you attend.

Cost £150 + VAT for all three with as many people as you want attending from your organisation.

Full course material – another £150.00 + VAT.

Course information link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/courses-and-seminars.html

Course booking form link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/zoominar-fixed-costs-choose-places.html

CPR 16.3(3) correctly states that in a claim for personal injuries, other than those arising from a Road Traffic Accident which occurred on or after 31 May 2021, a Claimant must state in the Claim Form whether the amount which they expect to recover as general damages for pain, suffering and loss of amenity is –

(a) not more than £1,500; or

(b) more than £1,500.

That of course reflects the fact that, outside the field of Road Traffic Accident matters, that is now the small claims limit in personal injury work.

Practice Direction 7A 3.5 has not been updated and reads:

“3.5 If a claim for damages for personal injuries is started in the County Court, the Claim Form must state whether or not the claimant expects to recover more than £1,000 in respect of pain, suffering and loss of amenity.”

Such failure to look at related Civil Procedure Rules and Practice Directions, and update them where necessary, is common.

Form N1A – Notes for Claimant on completing a Claim Form has not been updated either and still refers to having to say whether the damages for pain, suffering and loss of amenity are either:

- ‘not more than £1,000’ or

- ‘more than £1,000’.

CPR 16.3 provides that the Claimant must, in the Claim Form, state:

“(a) the amount of money which he is claiming;

(b) that he expects to recover—

(i)not more than £5,000;

(ii)more than £5,000 but not more than £15,000; or

(iii)more than £15,000; or

(c) that he cannot say how much he expects to recover.”

The requirements in CPR 16.3(3) already referred to is in addition to the requirements of CPR 16.3(1) and (2) in relation to a personal injury claim.

CPR 16.3(A) deals with personal injury claims arising from a road traffic accident where the small claims limit is £5,000.

Here is the relevant Section of Form EX50 – Guidance – Civil Court Fees – updated 6 October 2023.

Civil court fees (EX50) – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Here is the overview:

This guide sets out a selection of civil court fees. See the full list of fees charged in the civil and family courts (EX50A).

The full lists of all court fees are contained in statutory instruments (SIs) known as fees orders and can be found at www.legislation.gov.uk

The court fees set out on this page apply to, and are the same in, the High Court and in county courts and family courts, unless otherwise stated. Your local court will be able to help you identify any fee not covered here.

Find out how to pay a civil or family court fee, get help with fees or get a refund.

Issuing claims

Money claims (civil fees order 1.1 to 1.2)

To issue a claim for money, the fees are based on the amount you are claiming, plus interest.

| Value of your claim | Fee |

| Up to £300 | £35 |

| More than £300 but no more than £500 | £50 |

| More than £500 but no more than £1,000 | £70 |

| More than £1,000 but no more than £1,500 | £80 |

| More than £1,500 but no more than £3,000 | £115 |

| More than £3,000 but no more than £5,000 | £205 |

| More than £5,000 but no more than £10,000 | £455 |

| More than £10,000 but no more than £200,000 | 5% of the value of the claim |

| More than £200,000 | £10,000 |

The bands of valuing the claim do not reflect the different tracks, that is the Fast Track and the Intermediate Track.

The band that encompasses them simply reads:

“More than £10,000 but no more than £200,000”

In a potential Fixed Recoverable Costs scheme case, do you have to give a statement of value of between £25,000 and £100,000, or what?

What court fee do you then pay?

5% of £100,000, even if the true range is say £30,000 to £60,000?

Parliament has a committee which constantly looks for errors in Statutory Instruments and inconsistencies between different Acts of Parliament and Statutory Instruments etc.

Surely it is time the Civil Procedure Rule Committee had such a sub-committee.

In fact, it may be better to put that task out to an external body as regrettably, the Civil Procedure Rules Committee inspires confidence in almost no one.

FIXED COSTS EXTENSION: PROPOSED RULE AMENDMENTS

Fixed Costs Zoominars

I am running three Fixed Costs Zoominars on the following dates:

– Tuesday, 16 January 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 19 March 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 14 May 2024: 4pm to 5pm

Recordings of the Zoominars will be sent whether or not you attend.

Cost £150.00 + VAT for all three with as many people as you want attending from your organisation.

Full course material – another £150.00 + VAT.

Course information link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/courses-and-seminars.html

Course booking form link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/zoominar-fixed-costs-choose-places.html

In Issue 201 in my piece – FURTHER FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS CHANGES – at Pages 1595 to 1599, I set out the minutes of the Civil Procedure Rules Committee in relation to the Extension of Fixed Recoverable Costs, arising from their meeting of 3 November 2023.

Here, I analyse those proposed changes in more detail.

CPR 26.7(1)(a) is to be amended to replace the word “when” with the word “after” so that the new rule will read:

“CPR 26.7. (1) Subject to rule 26.8, the court shall allocate the claim to a track and, where applicable, assign it to a complexity band –

(a) after all parties have filed their directions questionnaire; (my bold).

The intention is to enable the court to allocate the claim to a track and, where applicable, assign it to a Complexity Band on the same occasion, but in a particular order.

CPR 26.9(10)(a) and (f) are to be amended and deal with track allocation in Clinical Negligence cases and a new definition regarding claims against Police authorities respectively; the final wording has not yet been published.

CPR 28.2(1) is subject to further revision, but that first revision does not reflect the usual practice that in Fast Track cases, Directions are given at the same time as allocation.

It was agreed that the mandatory obligation is to give directions but that the rule could be further revised to separate out Fast Track and Intermediate Track cases.

It is to be made discretionary to fix a Case Management Conference, and this is to be achieved by the word “may” replacing the word “shall” in CPR 28.12.

A clarificatory amendment concerning expert reports was proposed by expanding rule 28.14(c) with a new (c)(i) and (ii) which are designed to set out what is and is not included within the 20-page limit.

New (c)(i) will provide that the expert’s description of the issues on which they are instructed to give their opinion, the conclusions they have reached and the reasons for those conclusions, are included within the 20 page limit; but new (ii) will expressly provide that the expert’s CV and any supporting materials to which the reasons for their conclusions refer, are added to the existing list of items (comprising any necessary photographs, plans and academic or technical articles attached to the report) are excluded.

Disclosure

The current practice is to only have Case Management Conferences in Fast Track cases by exception and the view was that that rule should remain.

New CPR 31.5 arises “more acutely” now that there are three applicable tracks, and because it now applies to the Fast Track, which was not previously the case.

Consequently, the disclosure provision under sub-rule (1) would be deleted and sub-rule (2) will be redrafted so that it is limited to the Intermediate Track and the Multi Track.

Sub-rule (3) will be amended to add the words “if any” before the words “party must file and serve a report”.

Thus, the new rule will read:

(3) not less than 14 days before the first Case Management Conference, if any, each party must file and serve a report verified by a Statement of Truth, … (my bold)

Contracting Out

CPR 45.1(3)(b) is effectively scrapped as it will be amended to include an exception to the ban on Contracting Out if

“the paying party and the receiving party have each expressly agreed that this Part shall not apply”.

The Civil Procedure Rules Committee states that the intention is to make it clear that when a contract allows for it the Civil Procedure Rules in this area can be disapplied, and that this has been incorporated in light of the decision of the Court of Appeal in

Doyle v M & D Foundations & Building Services Ltd [2022] EWCA Civ 927 (8 July 2022).

The logic of this does not stack up as the Judgment was delivered well over a year before the new Civil Procedure Rules banning Contracting Out came in.

It appears that the rules were drafted without anyone realizing or being aware of that Court of Appeal decision, which attracted a lot of publicity amongst lawyers.

Inquest Costs

CPR 45.1(9) is to have added to it:

“This Part does not apply to costs incurred in respect of, or in connection with, inquest proceedings”.

Restoration Proceedings

A new CPR 45.15A allows for the costs of Restoration Proceedings and will be included in the Costs Tables in the rules.

Consequently, CPR 45.56 dealing with the recoverability of Costs Restoration Proceedings in Noise Induced Hearing Loss claims will be omitted, as unnecessary when the new rule is in the Tables.

Advocate’s fees on late settlement or vacation

In the Fast Track, 100% of the Advocacy fees will be recoverable if the case settles the day before trial or on the day of the trial.

If it settles two days before trial, then 75% of the fee will be recoverable.

Before that, nothing is recoverable.

In the Intermediate Track, the 100% rule will apply in the same way, that is if the case settles on the day before trial or on the day of the trial.

However, in the Intermediate Track, 75% of the fee will be recoverable if the case settles five, four, three or two days before trial.

If settled more than 5 days before trial, then nothing is recoverable.

The Tables will be amended accordingly.

INTERMEDIATE TRACK BANDING: ANOTHER DRAFTING ERROR

Fixed Costs Zoominars

I am running three Fixed Costs Zoominars on the following dates:

– Tuesday, 16 January 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 19 March 2024: 4pm to 5pm

-Tuesday, 14 May 2024: 4pm to 5pm

Recordings of the Zoominars will be sent whether or not you attend.

Cost £150 + VAT for all three with as many people as you want attending from your organisation.

Full course material – another £150.00 + VAT.

Course information link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/courses-and-seminars.html

Course booking form link – https://kerryunderwood.co.uk/zoominar-fixed-costs-choose-places.html

Into which Complexity Band does an Intermediate Track claim go where only one issue, liability, is in dispute, but the trial will last two days?

Assignment within the Intermediate Track is dealt with by CPR 26.16 which has within it Table 2 and the minimalist list of factors governing Complexity Band assignment.

The fact that the trial will last longer than one day takes it out of Complexity Band 1, as that is factor (b) in Complexity Band 1.

Clearly, the matter could go into Complexity Band 4 as that has no restrictions save that the matter be unsuitable for assignment to Complexity Bands 1 to 3.

The matter is unsuitable for assignment to Complexity Band 1 as it will last longer than one day.

Clearly it ought to go into Complexity Band 2 or 3, where a two-day trial can be accommodated, but they state that they are restricted to claims where more than one issue is in dispute.

That is obvious madness, but that is indeed what it states.

The High Court recently said the Civil Procedure Rules are not the law of the country, but rather a commentary on them, and we can agree that as commentaries go, they are virtually unintelligible at times.

My view is that a court could take a purposive approach, as they did in the Qader & Esure case and add in words after the first word “any” along the following lines:

Any “Claim where only one issue is in dispute but which is expected to last more than one day; and”

I am grateful to Simon Gibbs, author of the excellent blog for pointing this further drafting error out to me.

COURT OF APPEAL ALLOWS FORCED ADR AS CIVIL CLAIMS IN FREEFALL

Courts Can Force Parties Into Alternative Dispute Resolution: Halsey Decision Obiter Says Court Of Appeal In Obiter Decision

In

Churchill v Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council [2023] EWCA Civ 1416 (29 November 2023)

the Court of Appeal, in a decision that has been subject to savage criticism, held that the courts can force parties to engage to Alternative Dispute Resolution by staying the action, and thus, effectively ending the proceedings unless and until non-court based processes are followed.

Here, the Court of Appeal declined to stay the action to force the claimant to use the defendant council’s internal complaints procedure, stating that it “may not be the most appropriate process for an entrenched dispute of this kind”.

The case involved a claim in nuisance relating to Japanese knotweed, allegedly spreading from the council’s land onto the claimant’s private property.

The council argued that the claimant should have followed Alternative Dispute Resolution options, including the council’s own internal complaints procedure, before bringing court proceedings.

The lower court dismissed the council’s application but gave permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal held that the lower court was not bound by the Court of Appeal decision in

Halsey v Milton Keynes General NHS Trust [2004].

The Deputy District Judge had referred to that case and stated that he was bound to follow the statement in that case that

“to oblige truly unwilling parties to refer their disputes to mediation would be to impose an unacceptable obstruction on their right of access to the court”.

The Court of Appeal said that the relevant paragraphs in the Halsey case were not part of the essential reasoning of the case and did not bind the judge to dismiss the council’s application for the stay, in other words they were obiter.

One can imagine the reaction of the Court of Appeal to a Deputy District Judge taking that view and stating:

“I am ignoring the Court of Appeal decision as the relevant part was not part of its essential reason”.

Ironically, given that the Court of Appeal did not impose a stay in this matter, their comments are also obiter and not binding on other courts.

Here the Court of Appeal had this to say:

“The court can lawfully stay proceedings for, or order, the parties to engage in a non-court-based dispute resolution process provided that the order made does not impair the very essence of the claimant’s right to proceed to a judicial hearing and is proportionate to achieving the legitimate aim of settling the dispute fairly, quickly and at reasonable cost.”

Relevant factors include the form of Alternative Dispute Resolution being proposed and whether the parties were legally represented or advised, and whether the nature of the process contemplated would be relevant.

COMMENT

A poor decision which should be overturned by the Supreme Court or Parliament.

No one should be forced out of the court process. The court has the remedy in costs to punish parties who unreasonably refuse to mediate or engage in Alternative Dispute Resolution.

The ludicrous suggestion, rejected by the Court of Appeal, that a council should be able to force a claimant bringing an action against it to use its own complaints procedure, and thus, be judge and jury in its own case, is a very dangerous concept.

Very many court actions are against the state or emanations of the state and any restriction on the power of the citizen to challenge the power of the state should be utterly rejected in the strongest terms by all courts at all levels.

The concern is that as the Civil Justice System falls apart, or has fallen apart, the pressure will be on citizens to do anything other than use the courts.

There has been a massive slump in the number of proceedings issued generally, and the Small Claims Portal notoriously has a backlog of 385,000 cases.

Land Registry applications take two years.

Small claims take 55 weeks until the first hearing.

The Probate Registry is under investigation by the House of Commons Justice Committee for its delays.

The courts should look to heal themselves before forcing people into non-court processes.

Supreme Court Workload Slumps

The number of Supreme Court judgments delivered in 2022-23 was a third lower than the previous year, the court’s annual report has revealed.

A total of 38 rulings is the lowest number since 2018-2019.

In 2021-22 the court delivered 56.

Meanwhile the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council almost doubled its delivered judgments during the same period, to 60 compared with 34 the year before.

Seven UK Supreme Court and four Judicial Committee of the Privy Council judgments were not unanimous.

In 2022-23, the UK’s highest court decided 273 permission to appeal applications with 70 applications granted permission.

Of the permission to appeal applications filed with the Supreme Court, 24 were considered public law and human rights cases.

They outnumbered all other topics, including commercial – 17, and family – 15.

Financial statements reveal the UK Supreme Court and four Judicial Committee of the Privy Council total expenditure in 2022-23 was £13,116,000, £722,000 less than the previous year. This included £7,408,000 in staff costs.

Operating income, which includes court fees and contributions from UK court services, totalled £8,087,000.

Research published by Thomson Reuters last month showed that the UK Supreme Court has come to deal almost exclusively with civil cases.

The number of cases filed increased 23% last year to 226, with civil cases accounting for 98%, up from 76% – 168 out of 220, in 2013-14.

Just 2% of cases filed were criminal cases last year, versus 24% 10 years ago.

385,000 Backlog On Personal Injury Small Claims Portal: House Of Commons To Investigate

The Ministry of Justice is investigating why thousands of claims appear to have stalled in the whiplash portal.

Around 385,000 claims that were started on the Official Injury Claim system since its launch remained ‘unresolved’ at the end of September, according to the department.

In its response to the justice committee’s concerns about the backlog, the Government agreed that timely progression of cases is something officials are ‘investigating in detail’.

The response added:

“Whilst the majority of claims proceed through OIC towards settlement, there are an increasing number of claims sitting on the system where no positive action to move them forward has been taken for some time and could, therefore, be considered as dormant.”

The committee reported in September that only a quarter of cases had reached settlement, despite the portal being active since May 2021.

The average time taken to settle a claim is 251 days. This was predicted to increase further as more complex cases came through the system.

The Government response stated that this average has indeed risen to 270 days, and for represented claimants it is higher still, at 327 days.

The Ministry of Justice said that the tranche of stalled claims includes those which have received a denial of liability and which the claimant has chosen not to pursue any further.

Many were also halted pending the result of the Rabot case on mixed injury claims, which is due to be heard in the Supreme Court in February 2024.

The response added:

“MoJ agrees that more work needs to be undertaken to better understand the flow of claims through the OIC process. Additional data will be published from January 2024 to help to provide greater clarity on the impact of dormant claims on outstanding claim volumes.”

The committee’s report also recommended that the Government establish how exactly the estimated £1.2bn savings from the reforms have been passed onto motorists by insurers.

The Civil Liability Act, which formed the basis for the reforms, requires the Treasury to report by April 2025 on the savings achieved.

The Government’s response indicated that this work has already begun, but there are no commitments about bringing forward deadlines for publishing this research.

Legal Services Board Proposes 14% Rise in Its Annual Budget

The Legal Services Board, which is the overall regulator for all legal services. proposes that its budget for the year be increased by 14%.

This will see it rise by £650,000 to £5.33 million a year.

This Board is funded entirely by regulated members of the legal profession, totalling 191,162 authorized individuals.

An eight-week consultation on the budget increase will begin in January 2024 ahead of a final business plan and budget being presented for approval in March 2024.

Justice Committee Of House Of Commons To Examine Probate Delays

The House of Commons Justice Committee is enquiring into delays in the probate system following the waiting time for grants of probate doubling between April 2022 and April 2023.

The Committee noted that lawyers are routinely advising clients to expect at least a nine-month delay, with delays often considerably longer than that.

The Committee will hear evidence on capacity, resources and delays across the probate service and the impact of digitisation and centralisation, including the effectiveness of the online probate portal.

The work of the Probate Registry will be examined closely; the Justice Committee wishes to hear from individuals as to their experience of applying for probate and how beneficiaries, executors and the bereaved are supported through the process, and how they are protected from rogue traders.

Written submissions must be made by 22 January 2024, with witnesses being called to give evidence after that.

Sir Bob Neill, chair of the committee, said:

“Concerns over probate have risen sharply over the last five years, with the waiting time for probate almost doubling in the last financial year alone. It is right the justice committee examine the reasons behind this, the consequences and takes evidence on the issues of capacity and resourcing.

Families across the country, have faced challenges in navigating the probate system, with reports of rogue traders and poor practice, as well as significant delays. My committee wants to examine how the administration of probate could be improved for people who are already coming to terms with the loss of a loved one.”

In October 2023, a Law Society commissioned survey showed that nearly two thirds of lawyers believed that online portals had increased delays in granting probate.

There was a widespread agreement that the process is taking longer than the paper-based system.

Ministry Of Justice Consultation On Implementing Increases To Selected Court And Tribunal Fees

On 10 November 2023, the Ministry of Justice published a consultation, which seeks views on proposals to deliver increases to selected court and tribunal fees:

Increasing 202 court and tribunal fees by 10%

These fee increases will be delivered in spring 2024, following the expansion of the Help with Fees remission scheme in late 2023.

The list of fees selected for increases can be found in Annex A of the consultation document.

Establishing routine updates to fees every two years

It proposes to make inflation-based increases to selected fees every two years and will review the costs underpinning fees to identify any fluctuations that require reflecting in the corresponding fee itself.

Where the Ministry of Justice becomes aware of reduced costs, fee updates in advance of each two-year interval will continue to be made, to prevent any non-enhanced fees over-recovering their cost.

It proposes to enhance, setting a fee above its cost, fee 4.1 under the Magistrates’ Court Fees Order 2008, which relates to proceedings under the relevant regulations regarding an application for a liability order.

The Ministry of Justice looks to retain the fee at 50p. A separate affirmative statutory instrument would be required, which the Ministry of Justice intends to introduce by the end of March 2024.

Responses should be submitted by 11.59 pm on 22 December 2023 via post to Fees Policy Team, Ministry of Justice, 102 Petty France, London, SW1H 9AJ or via email to mojfeespolicy@justice.gov.uk.

Source: Ministry of Justice: Implementing increases to selected court and tribunal fees (10 November 2023).

Civil Claims Issued

Civil claims issued in September 2023, the last month for which figures are available, showed a decrease of 11.9% as compared with March 2023.

Defended claims in September 2023 dropped to 10.1% as compared with March 2023.

Small Claims – 55 weeks to trial

In September 2023, the last month for which figures are available, the average time taken to the trial or first small claims hearing was 55.2 weeks, compared to 51.4 weeks in March 2023.

Thus, in six months the number of civil claims has dropped sharply but the delay in hearing even a small claim has increased sharply.

Source: His Majesty’s Courts And Tribunals Service Management Information Tables

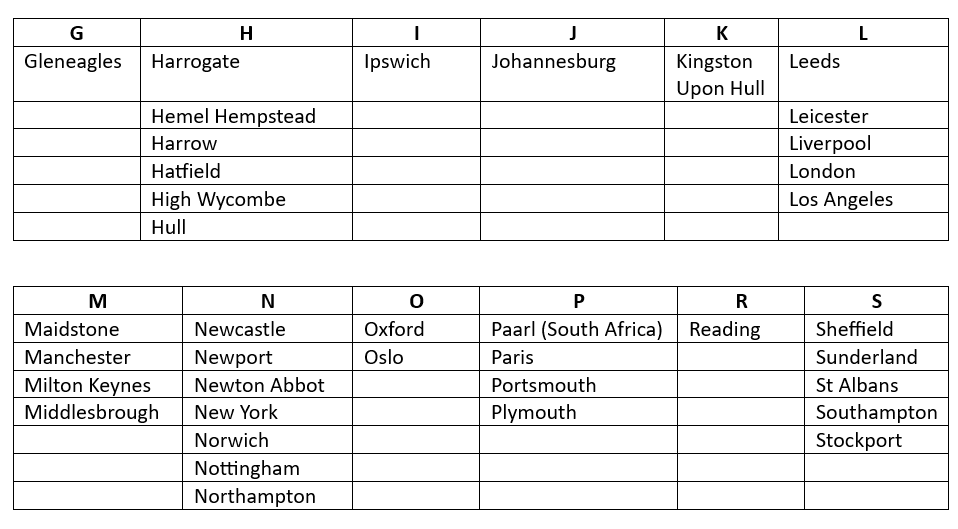

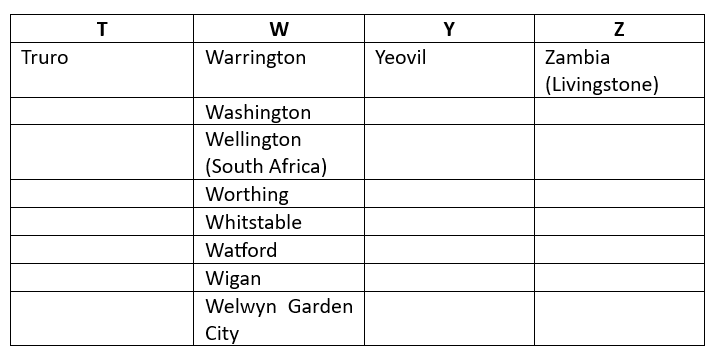

TOWNS AND CITIES I HAVE SPOKEN IN

As the final leg of the final tour comes to an end, those long train journeys and evenings in hotels got me thinking about cities and towns where I have spoken.

I am sure I have forgotten some but here goes:

FIXED COSTS: LAST FEW COURSES!

CIVIL LITIGATION: MANCHESTER, LIVERPOOL, LEEDS, AND BIRMINGHAM

PERSONAL INJURY: MANCHESTER, LIVERPOOL, LEEDS, BIRMINGHAM AND NEWCASTLE

The two Manchester Courses are live-streamed and can be viewed remotely. Same price.

Please book and email claire.long@lawabroad.co.uk with your details if you want to attend Manchester remotely – we can then send you the link.

Details of the Courses including dates are here, and can be booked here.

The changes are enormous and in place now and are retrospective for Civil Litigation, affecting all retainers where the case has not been issued.

The Civil Procedure Rules are a mess. You need to attend.

INTRODUCTION TO FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS

Kerry is currently undertaking a Nationwide Tour of courses.

Another utterly brilliant course from Kerry

Kerry is very knowledgeable and gives very clear answers.

Great to have the benefit and wisdom of Kerry.

Very informative and helpful.

Very good. Will be back for more.

Amazing

The introduction of fixed recoverable costs in relation to nearly all civil litigation claims valued at £100,000 or less represents the biggest change for civil litigators since the implementation of the Woolf Report, and the consequent introduction of the Civil Procedure Rules over 20 years ago.

These reforms relate primarily to civil litigation, but much personal injury work is caught by them.

In relation to costs, it is arguably the most significant change since lawyers were first allowed to charge for court work, that is since the Attorneys and County Court Act 1235, which I wrote about in Issue 42 at pages 123-124 – ATTORNEYS AND COUNTY COURT ACT 1235.

So that is arguably the biggest change in costs for 788 years.

Background

In his 2016 book – The Reform of Civil Litigation – Lord Justice Jackson wrote

Kerry Underwood’s prediction. In 2006, Kerry Underwood published the second edition of his book Fixed Costs. Chapter 1 began with a bold statement: “Fixed costs represents an opportunity to rescue a civil justice system that, like most public services, is in terrible trouble.” Chapter 1 predicted that fixed costs would spread quickly from the RTA scheme to other areas of litigation.

What was the position in 2009, when the costs Review began? The position was essentially the same as described in Underwood’s book.

After some phone calls and emails with Lord Justice Jackson I became heavily involved in this Review, resulting in the publication on 31 July 2017 of Lord Justice Jackson’s Supplemental Report

Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Supplemental Report Fixed Recoverable Costs

On 28 March 2019, the Ministry of Justice published its consultation paper:

Extending Fixed Recoverable Costs in Civil Cases: Implementing Sir Rupert Jackson’s Proposals

That consultation paper contained the Government’s proposals for implementing the reforms and needs to be read in conjunction with the final document, published on 6 September 2021 by the Ministry of Justice:

Extending Fixed Recoverable Costs in Civil Cases: The Government Response

All Change

Throw away your time recording system; forget work in progress, forget cost budgeting, and forget assessment proceedings.

Embrace contingent and conditional fees and get to grips with Part 36.

These are the lessons to be learnt from the field of personal injury where fixed recoverable costs have been in for 20 years.

The key points are that recoverable fees are the same irrespective of the level of the fee earner, solicitor or counsel, and irrespective of whether, or when, liability has been admitted.

There will be capped costs if the matte settles pre-issue, and an entitlement to those costs without contractual agreement.

Thus, the moment you write that initial stroppy letter to the other side, you have created a potential adverse cost liability for your client.

This does not arise in personal injury cases, due to the system of Qualified One-Way Costs Shifting, which does not apply in other civil work at present but is likely to spread.

Match or beat your Part 36 offer and you get a straight 35% increase in fees. Even if you are lucky enough to have a profit margin of 35% this doubles your profit; if your profit margin is 17.5%, it trebles your profit on that work.

There is much more to it than this, fixed recoverable costs will be the biggest change in the working lives of most civil litigators.

- Guideline Hourly Rates – irrelevant

- Seniority of lawyer – irrelevant

- Time spent – irrelevant

- Indemnity principle – irrelevant and does not apply

- Budgeting – irrelevant and does not apply

The whole purpose of the new system, and the abolition of indemnity basis for assessment etc, was specifically stated in the Government’s response to avoid the need of detailed assessment

“and the keeping of records to inform an assessment.” (my bold)

The indemnity principle

In

Nizami v Butt [2006] EWHC 159 (QB)

the court held that the indemnity principle did not apply to fixed recoverable costs cases, meaning that whatever the solicitor and own client retainer contained, or did not contain, the paying party had to pay the fixed recoverable costs.

In his 2017 Report, Lord Justice Jackson said, at paragraph 2.8:

“I have previously argued that, in relation to costs, the common law ‘indemnity principle [as compared with indemnity costs] served no useful purpose and should be abolished: see chapter 5 of my Final Report. That argument fell on deaf ears. In those circumstances, the CPR must make it clear that the indemnity principle has no application to FRC.[fixed recoverable costs]”

This rule does not prevent a challenge by the client to her or his own solicitor’s bill under the Solicitors Act 1974.

Fixed Recoverable Costs were originally proposed as part of the Woolf Report, and it was that Report which brought in the Civil Procedure Rules to replace the old Rules of the Supreme Court and County Court Rules which appeared in the old White Book and Green Book.

Lord Woolf said that there was no point in bringing in the Civil Procedure Rules without at the same time introducing Fixed Recoverable Costs, but, surprise, surprise, that is exactly what happened.

With effect from 1 April 2013, Fixed Recoverable Costs were introduced for most personal injury cases valued at £25,000 or less, and this flowed from Lord Justice Jackson’s first Report – Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Final Report published in January 2010.

These current changes are heavily based on Lord Justice Jackson’s Supplemental Report:

Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Supplemental Report Fixed Recoverable Costs

which was published in July 2017.

The 1 October 2023 changes are achieved by the Civil Procedure (Amendment No. 3) Rules 2023, Statutory Instruments 2023 No.788 (L.8) which appears at Annexure A.

There is an Explanatory Memorandum to the Civil Procedure (Amendment No. 2) Rules 2023, Statutory Instruments 2023 No. 572 (L.6) and that appears at Annexure B.

The156th update – Practice Direction Amendments – supplement the changes to the Civil Procedure Rules in relation to Fixed Recoverable Costs and appears at Annexure C.

SCOPE

Virtually all civil litigation in England and Wales valued at £100,000 or less is subject to the new Fixed Recoverable Costs Scheme.

I set out below the exceptions, and all other claims allocated to the fast track or the intermediate track will be subject to the new scheme.

I deal with the allocation criteria in the section Tracks, Bands and Stages.

EXCEPTIONS

The main areas excluded are:

– Judicial Review;

– A Claim for damages in relation to harm, abuse or neglect of or by children or vulnerable adults,

including historical child sexual abuse

– Mesothelioma and Asbestos-related lung disease claims

– Military claims;

– Clinical Negligence, except where breach of duty and causation admitted and where the claim

would have been allocated to the intermediate track

– Actions against the Police involving an intentional or reckless tort, or relief or remedy under the

Human Rights Act 1998.

This exclusion does not apply to a road accident claim arising from negligent police driving, an

employer’s liability claim, or any claim for an accidental fall on police premises.

– Intellectual Property – costs rules governing scale costs in the Intellectual Property and

Enterprise Court will remain the same as they are present but will move from Section IV of

Part 45 but will be move to Section VII of Part 46 – Costs Special Cases

– Housing Disrepair – inclusion delayed until at least 2025.

– A claim that the court could order to be tried by jury if satisfied there is in issue a matter set out in

section 66(3) of the County Courts Act 1984 or section 69(1) of the Senior Courts Act 1981.

– Part 8 claims.

– Solicitors Act 1974 claims.

The court has a general discrepancy who allocate complex claims with a value of under £100,000 to the multi-track, thus removing them from the Extended Fixed Recoverable Costs scheme.

There is no guidance on what will be cast as a complex case, and this is likely to lead to extensive satellite litigation.

It is of interest as to how the exceptions have been achieved.

New CPR 26(10) reads:

“(10) A claim must be allocated to the multi-track where the claim is –

- A mesothelioma claim or asbestos lung disease claim;

- one which includes a claim for clinical negligence, unless both breach of duty and causation have been admitted;

- a claim for damages in relation to harm, abuse or neglect of or by children or vulnerable adults;

- a claim is one the court could order to be tried by jury if satisfied that there is in issue a matter set out in section 66(3) of the County Courts Act 1984 or section 69(1) of the Senior Courts Act 1981; or

- a claim against the police which includes a claim for—

- an intentional or reckless tort; or

- relief or a remedy in relation to a breach of the Human Rights Act 1998.”

Thus, as a matter of principle, those matters go into the Multi Track, and are unlikely to be in any extended scheme of Fixed Recoverable Costs as it is not a matter of value of the claim, but rather of principle.

However, in relation to some other exclusions, such as those relating to Military Claims, and Housing Disrepair and associated claims, the exclusion is not by this method.

My view is that such claims will be brought within the Fixed Costs regime, or a tailor-made bespoke scheme for such claims, sooner rather than later, especially as in Military Claims the defendant and potential paying party is the state, and in Housing Disrepair often a Local Authority.

In relation to Housing Disrepair and associated claims, they have been specifically excluded for a period of two years, but with a view to them being brought in at some stage.

Housing claims are excluded from both the fast-track Fixed Costs regime and the intermediate track Fixed Costs regime and that is by virtue of new CPR 45.1(4) which reads:

(4) Section VI and Section VII of this Part do not apply to a claim or counterclaim which relates,

in whole or in part, to a residential property or dwelling and which, in respect of that property,

includes a claim or counterclaim for—

(a) possession;

(b) disrepair; or

(c) unlawful eviction,

save where the claim or counterclaim in respect of the residential property or dwelling arises

from a boundary dispute.

It will be seen that housing claims are defined as including any claim or counterclaim which relates, in whole or in part, to a residential property or dwelling, in which in respect of that property, includes a claim or counterclaim for:

(a) possession;

(b) disrepair; or

(c) unlawful eviction;

save where the claim or counterclaim arises from a boundary dispute.

Although these matters are excluded from both the fast track and intermediate track Fixed Costs scheme, the Government has announced that their inclusion has been delayed for a period of two years, as it was originally intended to bring them in.

It should be noted that it is only the new Rules on Fixed Costs which do not apply to these claims, and the remainder of the new Rules, including those relating to allocation do apply.

The provisions of Part 2 of CPR 45 still apply, and they provide for Fixed Costs for, among other things, undefended possession claims and accelerated possession claims – see new CPR 45.16(2)(c) to (f).

Note that it is only residential property matters which are excluded from the new Fixed Costs regime, and therefore, all matters relating to commercial property are within the new Fixed Costs scheme if proceedings are issued on or after 1 October 2023.

Note also that by virtue of new CPR 45.1(5) where a claim relates in part to a residential property or dwelling, and that part of the claim is concluded or discontinued, the exclusion from the Fixed Costs regime in both the fast track and the intermediate track shall continue to apply to the remainder of the claim.

IMPLEMENTATION DATE

Sunday, 1 October 2023.

Any case, whether civil or personal injury, issued by 30 September 2023 can never be subject to the new Fixed Recoverable Costs scheme, either in relation to costs or procedures.

THE COURT’S POWERS TO DISAPPLY FIXED RECOVERABLE COSTS

Once a claim is allocated to the fast track or intermediate track, the court’s power to award costs is limited by CPR 28.8 to awarding fixed costs in accordance with Practice Direction 45, so once a claim has been allocated and assigned, the court does not have discretion to remove a case from the Fixed Recoverable Costs regime unless it re-allocates it.

The court retains discretion to decide the incidence of costs in CPR 45.1(2)(a), when they are paid, CPR 45.1(2)(b) and whether to order that one party pays some or all the other party’s costs, CPR 45.1(2)(c).

The court cannot order an increase or reduction to the Fixed Recoverable Costs figures other than as provided for in the rules, CPR 45.1(3).

Despite these rules, CPR 45.9 states that the court may consider a claim for costs exceeding the Fixed Recoverable Costs where there are exceptional circumstances making it appropriate to do so.

There is no guidance as to what might constitute exceptional circumstances, so this will likely be the subject of case law once the new rules come into force.

If a party does seek costs in excess of the Fixed Recoverable Costs but fails to achieve an order for more than 20% of the Fixed Recoverable Costs, they will only receive the lower of the Fixed Recoverable Costs or the assessed costs and may not be able to recover their costs of assessment, CPR 45.11.

TRIGGER DATES

PERSONAL INJURY

Date of cause of action, and in disease claims, the date of the letter of claim.

Consequently, existing personal injury actions, and those where the accident occurs on or before Saturday, 30 September 2023 are unaffected, and can be proceeded with as before.

This gives personal injury lawyers, who are very well acquainted with Fixed Recoverable Costs, extra time to plan and work out a policy moving forward in relation to accidents occurring from 1 October 2023 onwards.

Virtually all personal injury actions, except for the exceptions listed above, are already covered if the damages are £25,000 or less, and although there are changes to the Fast Track for personal injury matters, personal injury lawyers will take these in their stride.

The key development for personal injury lawyers is the fact that claims valued at £25,000 to £100,000 will now be subject to Fixed Recoverable Costs, and will be in the new Intermediate Track, with its new rules and concepts.

Another introduction across the board, for both personal injury work and civil litigation, is the Bands of Complexity.

OTHER CIVIL LITIGATION

This is very different, and in all fields except personal injury, dealt with above, the trigger date is the date of the issue of proceedings.

All cases issued on or after 1 October 2023 are subject to Fixed Recoverable Costs.

Thus, general civil litigators, unused to Fixed Recoverable Costs, must deal with issues now.

In relation to civil litigation, but not personal injury work, the changes are effectively retrospective in that in relation to matters unissued by 1 October 2023 the new Regime will apply, even if the case came into the office say five years ago.

The main problem area in terms of costs is likely to be the solicitor and own client retainer and the agreement in relation to counsel’s fees.

In a case that has been proceeding for some time, but has not been issued, it may well be the case that the costs are already above the level of Fixed Recoverable Costs, even if the matter went to trial.

The solicitor and client may have entered into an hourly rate retainer on the basis that at least Guideline Hourly Rates would be recovered from the other side on success, subject to reasonableness and proportionality.

All that goes out of the window with Fixed Recoverable Costs which are determined by a combination of the stage reached and the value of the claim, or the amount of damages awarded by the court, or the amount of the settlement sum.

Time spent and the seniority of the lawyer are irrelevant and thus the costs will be recovered from the other side on a fundamentally different basis than that which solicitor and the client assumed to be the case when they entered into the retainer.

The same point applies in relation to counsel’s fees.

I deal below with the issue of solicitor and own client costs, and theoretically nothing changes, but in practice, everything changes.

In relation to civil litigation solicitors should look at the retainer in every single case which will be caught by the new Regime, and should meet the client, either live or virtually, to explain the changes, and, if necessary, to revisit the retainer.

Note carefully that all fast-track matters and intermediate-track matters will be in the County Court and thus the all-important provisions of Section 74(3) of the Solicitors Act 1974 apply.

There is no new law here, and any matter which will now be caught by the Fixed Costs Regime, and thus is in the fast-track or the new intermediate track, was always likely to be a County Court matter, and that would have been apparent when the solicitors were first instructed.

Any matter which was likely to be a High Court matter, and in the multi-track, is still likely to be allocated to the multi-track, and, whatever the value of the claim, Fixed Recoverable Costs have no place whatsoever in the multi-track.

The key difference is that when the solicitor and client entered into the retainer, the expectation would have been that the amount which could have been allowed in respect of each item as between party and party in the proceedings would be Guideline Hourly Rates, with reference to the hours spent, the seniority of the lawyer, and the location.

Thus, on defeat, a solicitor could charge the client the amount which could have been recovered from the other side on victory.

That changes overnight.

That sum will now be the Fixed Recoverable Costs sum, as that is the sum “which could have been allowed in respect of that item as between party and party in those proceedings”.

I deal with this below, but put simply if, when the retainer was entered into, the client did not specifically sign an agreement that the solicitor could charge more than the sum that could have been recovered, then that is that.

Further Areas of Uncertainty

Can that Agreement be Backdated?

On the face of it, the answer is yes in that the general law of contract is that parties can backdate an agreement and can have retrospective agreements.

This issue has arisen on many occasions in relation to Conditional Fee Agreements, and the courts have upheld the validity of retrospective Conditional Fee Agreements between solicitors and clients.

Thus, as a matter of pure law, the solicitor and client could enter into a new, retrospective retainer allowing the solicitor to avoid Section 74(3).

The problem will be one of informed consent; why would a client, fully informed of the issue, consent to a new, retrospective retainer, which would potentially cost them tens of thousands of pounds.

Can The Solicitor Terminate the Retainer If the Client Does Not Agree to The Variation?

My view is that the solicitor cannot lawfully terminate the retainer simply because Parliament has changed the law to mean that they will now recover from the other side less in costs than previously.

Had the Section 74(3) formalities been complied with at the outset, then the issue would not arise.

It is important to note that Lord Justice Jackson’s Supplemental Report:

Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Supplemental Report: Fixed Recoverable Costs

was published in July 2017.

Entirely by chance, that is just over six years ago, and the primary limitation period in general civil litigation is 6 years.

I know that that is not the whole story, as there are exceptions, but the general position is that any matter which arose by July 2017 will have been issued before 1 October 2023, due to limitation.

Consequently, a client on a Solicitors Act 1974 assessment will be able to argue that the solicitor was well aware that the Scheme of Fixed Recoverable Costs would be coming in for all claims valued at £100,000 or less and therefore should have insisted on the client opting out of Section 74(3) at that time.

Lord Justice Jackson’s Report contains specific figures, and uprated for inflation those are very much the figures effective 1 October 2023, and therefore the solicitors should have known at that stage the level of Fixed Recoverable Costs.

Does The Change Frustrate the Solicitor and Own Client Contract?

Essentially for the reasons given immediately above, my view is that it does not frustrate the contract, as the contract is still capable of being performed and the difference is that the client will recover different costs for the same case than previously thought.

The key issue will be that the shortfall between the recovered costs and the solicitor and own client costs will be significantly higher.

The contract is not frustrated, but rather the solicitor has made a bad bargain, and one that could have been avoided at the time by following the provisions of Section 74(3) of the Solicitors Act 1974.

Template Letter under Section 74(3)

KEY CLIENT ISSUES